*This essay has been amended/updated since its original publication.

In part 1 of this article series, I laid out a general schema for the way the pattern of purification, illumination, and perfection scales up fractally. That intro was presented more or less in the abstract, using my interpretation of some insights from St. Maximus the Confessor. A certain degree of ‘detached’ technicality was necessary at first to get the fractal structure across. But here in part 2, I’ll start applying that framework to the Gospel of John,1 where narrative elements will begin to fill the fractal scaffolding with living substantiality, lending it a more accessible and personal dimension.

A few key concepts

To kick off this exploration, I’d like to first take a moment to discuss the varied manner in which purification, illumination, and perfection are represented symbolically in John and also to lay out some concepts and terms that will be helpful throughout our study. (So a few more technical details up front – bear with me!) Probably the most important thing to keep in mind is the fact that – and you heard me say this several times in part 1, but it bears repeating – the symbolism we’ll be looking at isn’t a fixed or rigid system. The same fractal structure will show up differently in different situations. If we’re looking for symbolic relationships to repeat precisely in the same manner from instance to instance, we’ll never see the full scope of the patterns at hand.

The elements of our 6 - 7 - 8 triad are at times exemplified by specific people and at other times not. When specific personages are operative, it’s actually the 6 - 7 dyad that appears most often, with a kind of tacit 8. In these cases I’ll refer to the person exemplifying purification as the ‘purifier’ and the person serving the function of illumination as the ‘illuminator.’ Sometimes we notice the combined dynamic of these figures simply from having them both present at a scene or standing next to each other. At times only the purifier is present, with the symbolic function of illumination served by virtue of the event taking place on the Sabbath. Other times still, two figures are involved in a more active manner. For example, one person fetches the other, leading them to some important scene of action. The phrase I’ll use for this is ‘goes and gets’: person A (usually the illuminator) finds, leads the way for, or grants entry to person B (usually the purifier). In these cases, it's often necessary for the one being fetched to have waited somewhere else while some crucial action involving the other was taking place.

Additionally, there are what we might call ‘long-range’ instances of the 6 - 7 - 8 triad, where a connection is made between figures or events from different, seemingly disconnected narratives. Such cases are often part of a scaled-up 6 - 7 - 8 pattern, but they can also occur within the lower levels as well. Usually some key phrase or image will cue us to the fact that a connection is being drawn to a prior or upcoming narrative.

When we start to piece together the different levels of our fractal, we begin to notice something very interesting that St. John is doing in his gospel – he’s building a ladder. This is reflected more or less directly in what Jesus says to Nathanael after gathering the first few disciples: “Amen, amen, I say to you, you will see the sky opened and the angels of God ascending and descending on the Son of Man” (1:51).2 As we’ll see, this figurative ladder we can imagine upon which the angels ascend and descend connects the very lowest, foundational levels of reality up to the very highest. But the ladder is potentially not visible at first glance. In order to approach it ourselves, we must “come and see.”3

The first ‘big triad’

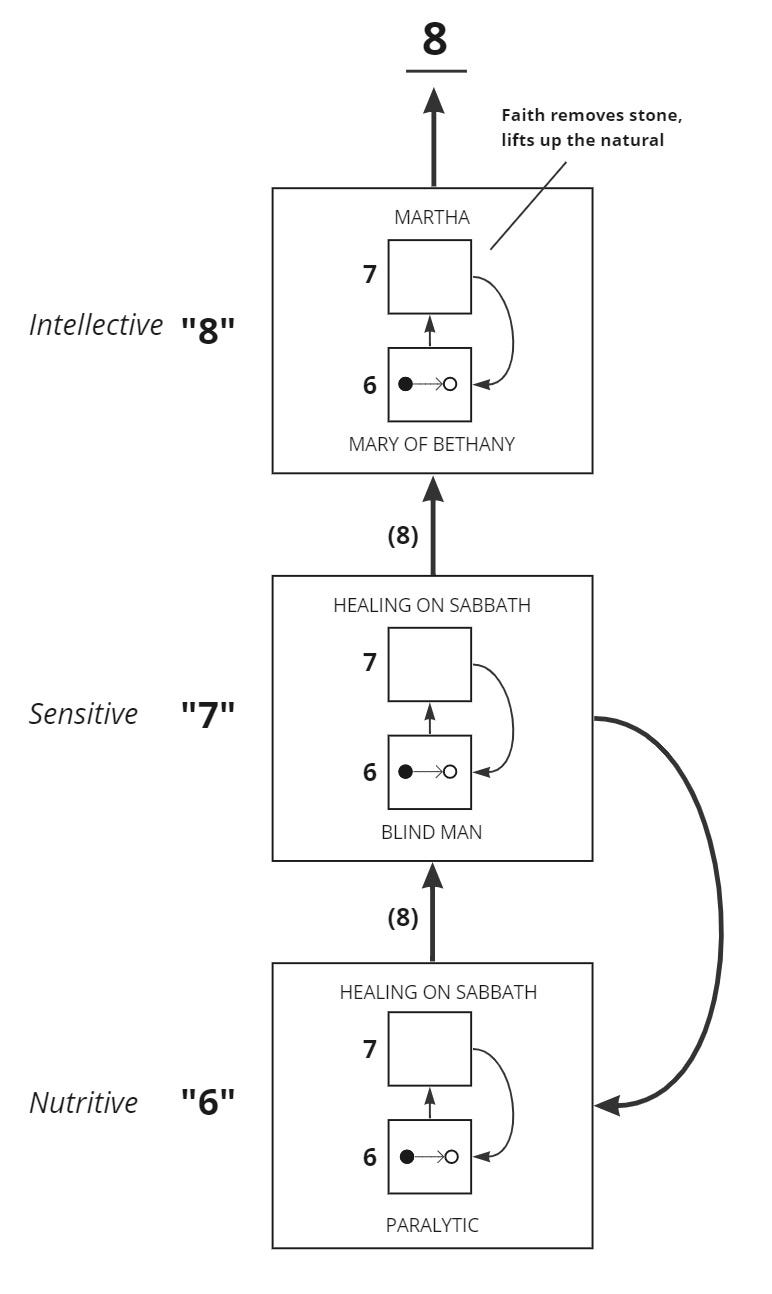

In the way I’ll look at it (and there are surely other ways), the ladder St. John depicts is composed of two ‘big triads,’ or 6 - 7 - 8 patterns containing smaller iterations. We might call those smaller iterations ‘little triads’ and the overall pattern consisting of both big triads together the ‘great triad.’ I’ll spend the remainder of part 2 on the first big triad.

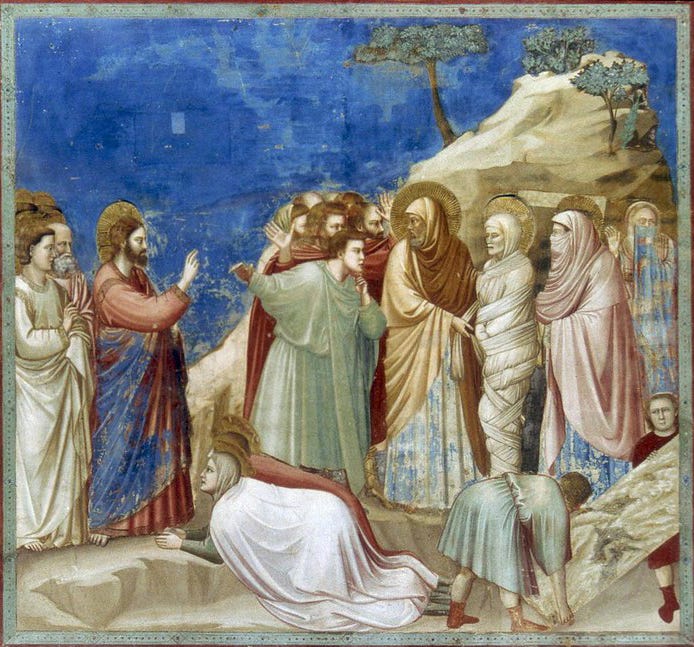

The first big triad emphasizes physical healings and has its climax in the raising of Lazarus. The second big triad has its climax in the Crucifixion and Resurrection of Christ. In a sense the first can be taken broadly to represent a lower, sensible aspect of the overall pattern and the second a higher, spiritual aspect (keeping in mind that, since the pattern is fractal, the two aspects contain each other and don’t constitute any sort of strict dualism, and additionally that all 6 - 7 pairs symbolically instantiate the body-spirit relationship, no matter what the level). At the immediate microcosmic level, Lazarus is the fleshly,4 sensible, or natural man, and at the macrocosmic level he stands for the sensible cosmos. The way St. John sequences the critical events leading up to and moving away from the Lazarus climax invites us to view them as rungs on the ladder leading to the restoration and lifting-up of the sensible world.

Connecting the healings

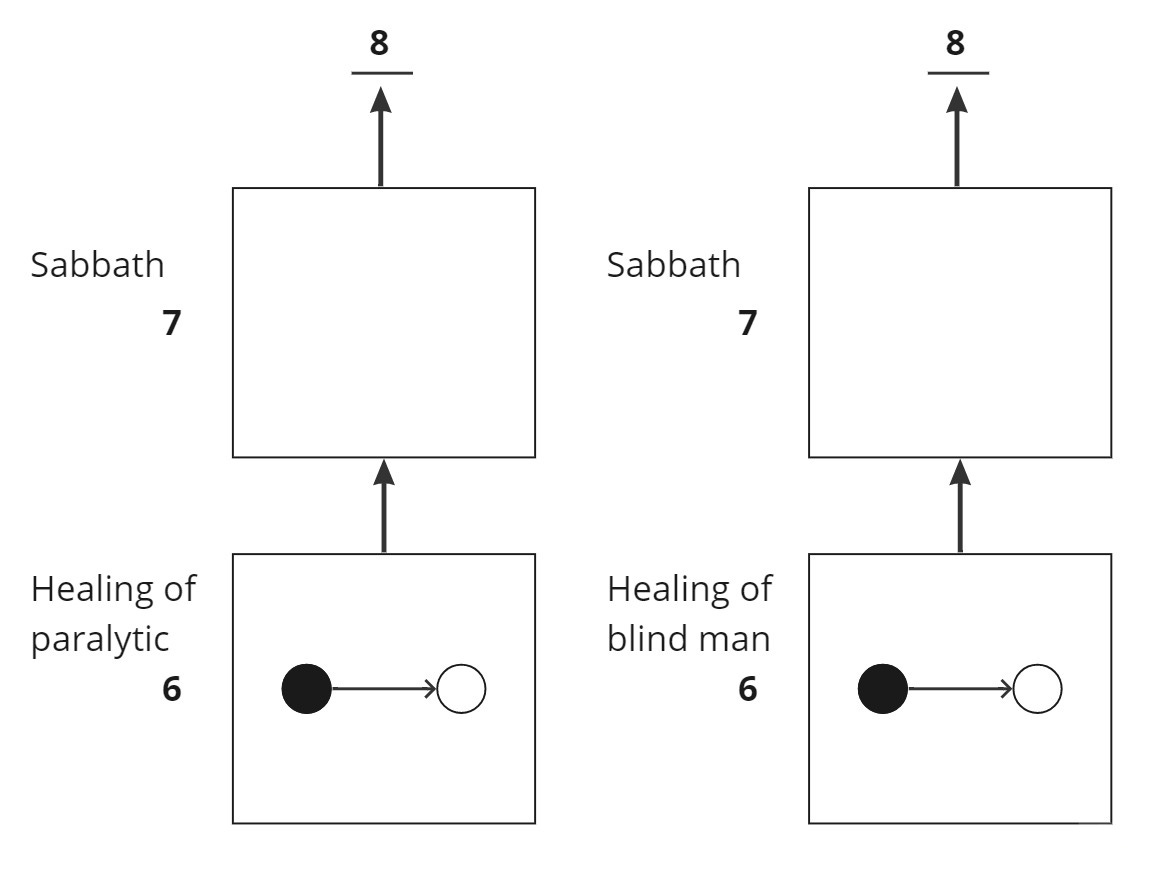

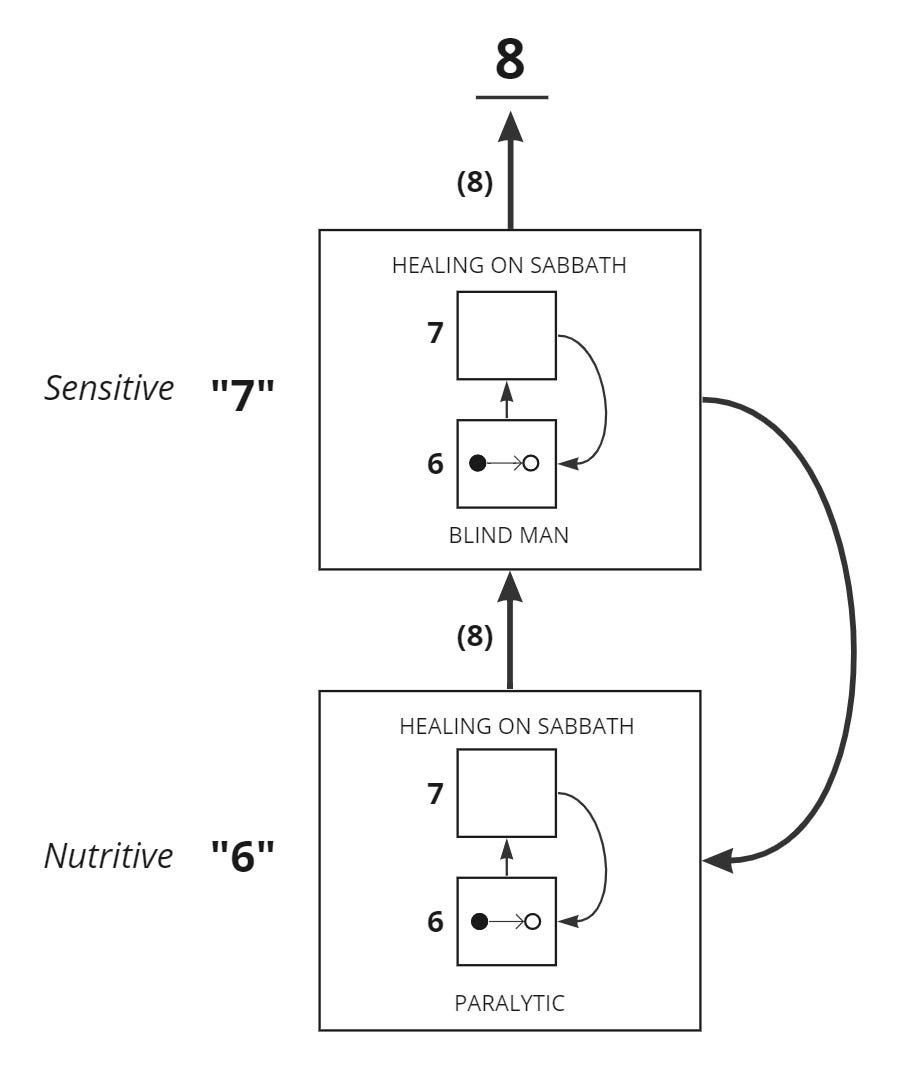

The first direct healing in John5 is performed on the paralytic at the Pool of Bethesda. Here at the first rung of the ladder, we have a healing of the physical body. The second healing, performed on the man born blind, is a restoration of physical sight. Both healings – or purifications – occur on the Sabbath, which as you’ll remember we’ve come to associate with illumination. So each healing separately can be thought of as a 6 - 7 pair within a 'little triad.'

Collectively these two definitely seem to form a long-range 6 - 7 pair themselves. The eyes are a ‘higher organ’ in relation to the body. We might call the level involved in the healing of the paralytic the nutritive or vital level. The physical body is the base level at which ensouled beings operate in the sensible realm, where physical material is drawn up into the individual and partakes in the corporeal organization of the living form. The eyes, on the other hand, are a preliminary window from the physical into the world of soul. Symbolically they can be used to represent the sensitive faculty of creatures, that faculty involved not only in raw sense perception, but also feeling and emotion.

In order to see whether or not we can in fact order the two healings into a larger 6 - 7 pair along these lines, we’ll need to examine some of the details from both narratives. Two critical components stand out that can be compared between the two: firstly the nature of the infirmity, specifically whether or not it is attributable to or associated with sin, and secondly what the healed person does or is told to do after the healing.

In the case of the paralytic, both of these components are addressed in one verse. Just after the paralytic takes up his mat and walks, Jesus tells him, “Look, you are well; do not sin anymore, so that nothing worse may happen to you” (5:14). With this statement we get the sense that the paralytic's bodily infirmity, or the corruption of the sensible, is bound up with sin. Though he’s told not to sin anymore, we aren’t given any further reply from the paralytic himself, and we’re left unsure as to whether he’ll heed Jesus’s command. Could he perhaps need or at least benefit from some further help?

In the case of the man born blind, the two critical details are different. At the very beginning of this story, while passing by the blind man the disciples ask Jesus, “Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?” (9:3) And Jesus replies, “Neither he nor his parents sinned; it is so that the works of God might be made visible through him” (9:4). This is a crucial and fascinating detail. Having not sinned, this man and his parents show they have brought to rest the practical activity of those who follow the Law. But until now they’ve not known the Word made flesh. “The Law is the shadow of the Gospel,”6 says St. Maximus, and we see that the blind man has indeed been living in a kind of shadow world, that is, until he is illumined by Christ. His sight comes to be in the world of the New Covenant, where the sensible no longer presents an unmovable obstacle to higher things. So with the obstacle removed, what does the blind man do when his eyes are opened, in addition to simply affirming that he can in fact now see? He professes belief. “Do you believe in the Son of Man?,” Jesus asks him. “Who is he, sir, that I may believe in him?” Jesus replies, “You have seen him and the one speaking with you is he.” “I do believe, Lord,” affirms the blind man (9:35-38).

So when we connect the two healings, we can reasonably conclude that they are related to each other in a quite profound way. The healed blind man and the healed paralytic collectively form an eyes-to-body relationship, where the higher organ is now positioned to open the way for, or to ‘go and get’ the lower. Turning back then to the paralytic’s story, a wonderful little detail jumps out. We find that, prior to being healed, the blind man had told Jesus, “Sir, I have no one to put me into the pool when the water is stirred up; while I am on my way, someone else gets down there before me” (5:7). He had no one to clear the way for him. In other words, sin kept getting in the way and he had no higher faculty to assist him. Jesus of course is the one who initially cures him, but we are given the subtle impression that it’s the opened, untainted eyes – also brought about by Jesus – that will be able to guide the body moving forward, to lead it again to the purifying waters.

You might recall at this point, if you read my Three Marys article where I presented Mary of Clopas (illuminator) first before moving onto Mary Magdalene (purifier), that while purification is step one, illumination is, somewhat surprisingly, equally necessary for further levels of purification to take effect. To repeat my Cormac Jones quote from part 1 of this series, “You don’t exhaust the need for purification before you already need a form of illumination.”7 This all goes back to the mutual interpenetration at the heart of all things fractal. And it’s essentially the same pattern seen here. Though the vital, bodily healing is step one, the sensitive healing brings about the higher member that clears a space for the lower member to function at a higher level. All that is to say, the healing of the blind man is a 7 to the paralytic’s 6. We can thus continue building our ladder accordingly. (Note that I’m now including a curved arrow leading from 7’s box to 6’s box in order to indicate the ‘goes and gets’ function often occurring with illumination).

The trio from Bethany

We’ve been leading up to the Lazarus climax, and we’re now at the point where Lazarus himself comes into the picture. St. John presents him to us alongside his two sisters Mary and Martha, all three of whom he makes a point of mentioning that “Jesus loved” (11:5). The trio’s particularly intimate relationship with Jesus is an indication that they will serve a very important function and that we should pay special attention to them. Since we’re tracking the building of a ladder, we should expect these figures to somehow embody still higher faculties than those we encountered in the previous two healings. This is in fact what we do find. Let’s briefly review the story to get a sense of it.

All are distraught to learn of Lazarus’s death, but it’s Martha who first believes Jesus’s pronouncement that Lazarus will soon be raised. She professes this while Mary – who St. John tells us is “the one who anointed the Lord with her perfumed oil and dried his feet with her hair” (11:12) – is away. When the stone is then removed from the cave where Lazarus’s body lies, Jesus declares to Martha, “Did I not tell you that if you believe you will see the glory of God?” (11:40). Shortly thereafter Lazarus is brought back to life.

In this remarkable sequence of events, we can ascertain that Martha and Mary form a higher-lower pair that collectively represents man’s intellective faculty. The lower level of the intellect might be thought of as the rational and the higher level the noetic.8 The noetic component of the human being encompasses many things, but we can describe it according to our schema by considering it the fulfillment and rest of the rational and an opening-up toward something beyond.

A brief aside on man’s role in creation

Before continuing the discussion around Mary and Martha, I feel the need to interject a brief aside. Take note of the fact that, up to this point, the rungs on the ladder which have been assembled represent faculties that man shares with other earthly creatures. The nutritive-vital faculty is the foundation of all things living. In Genesis 1 it’s the plants which first appear and operate on this level. Next come the animals with their sensitive faculty. Broadly speaking, this is where non-human earthly creatures cap out, so to speak. Now, on day six in Genesis, the Lord arrives at that creature in whom he implants the created image and likeness of his own Spirit, manifesting (at least in part) as the rational-noetic capacity. Since each stage of creation lays the groundwork for what comes next, the human microcosm thus has all these faculties – nutritive, sensitive, intelligent – folded into and united within his soul. In him they form a ladder from the material up to the spiritual. What is nutritive in man operates at the level of the plant, while what is intelligent in him operates at the level of, one might say, the angel. The human constitution traverses low and high, gross and subtle, common and exalted. For this reason he is given the role of mediator and world steward.

But man upholds this most important role only so long as he observes the Sabbath, the perimeter of grace, as it were, that circumscribes the human and all of nature below him. For this perimeter isn’t so much a wall as it is a doorway, a doorway to union between God and creation that it is man’s prerogative to leave open or to close. In order for man’s noetic capacity to fully function, the doorway must remain open. He must keep holy the seventh day. This means recognizing the boundary of his proper domain, where he is no longer in charge. It means giving up control and reaching up to God's outstretched hand. When man does this, he allows the Sabbath to remain the link between nature and supernature, “the full return to [God] of all creatures whereby he rests from his own natural activity toward them, his very divine activity,”9 in the familiar words of St. Maximus the Confessor.

Should he spurn the Sabbath, it is then man himself who forms a perimeter around the natural world, cutting the sensible off from the intelligible, denying himself and all other creatures access to their true mode of being. The noetic devolves into the merely rational, the sensible devolves into the fleshly and merely animal, and the nutritive, life faculty itself – for which the plants served as the original prototypes – is marred with the stain of death. Matter itself is corrupted; living potentiality succumbs to the cyclical returning-to-dust of corporeal forms. Such is the state of things in a world stuck on the sixth day. “The whole creation groaneth and travaileth in pain together.” That is, “until now” (Rom 8:22).

That “until now” of course refers to Christ’s incarnation on the earth, whereby through his sacrificial death and resurrection he restores the whole creation, from the very bottom of the chain of being up to man, and through man the link between the earth and the heavenly heights. Christ leads humankind and the world through these ‘stages of rectification,’ as we might call them, from the foot of creation up to the head, back to the open doorway of the seventh day. And beyond that: the eighth.

Back to the Bethany trio

Okay, I said it was going to be a brief aside, and it seems I’ve waxed voluble for several paragraphs. I hope you’re still with me! Now back to Mary and Martha.

So…we can take Mary to represent the lower intellective faculty, or rational man. This is indicated by the fact that she later tends to Jesus’s lower members, specifically his feet. With Mary temporarily absent (you’ll recall Martha goes to meet Jesus while Mary stays home), the lower rational faculty is ‘out of the way,’ so to speak, allowing Martha’s higher noetic intellect to operate unimpeded. Martha believes what Jesus tells her, and he reminds her of this right before the stone is removed from the tomb and Lazarus is called forth. Here we get the sense that unobstructed faith in the Savior is the very thing that removes the obstacle between man and God, the perimeter man had erected around nature which crippled and corrupted it and brought about death. Removing the barrier is shown to aid the elimination of death itself. So here we have the higher intellective faculty of creation connected all the way back down to the lowest and most fundamental, that element modeled first in the plants – namely, life. Life is restored through faith in Christ. And with the lowest rung on the ladder connected back up to the highest (or at least the highest in our first ‘big triad’), the whole human microcosm is restored. Lazarus is raised.

But it’s a little more complicated than the picture I’ve just painted. In assigning Martha the symbolic role of illumination, we must remember that illumination here serves the transition from the Old Covenant to the New. The chief illuminator in the Gospels, John the Baptist, tells us, “I did not know him [Christ], but the reason why I came baptizing with water was that he might be made known to Israel” (John 1:31). Focusing in on the phrase “I did not know him” is helpful in understanding the full symbolic significance of Martha, for we see that she in a sense “knew Christ” only with difficulty. She’s like a sleeping person roused who peers through the tired eyes of sleep at the rouser, struggling to discern their visage with clarity. We see this in the several attempts it takes her to properly comprehend the full magnitude of Christ’s power and identity. “Jesus said to her, ‘Your brother will rise.’ Martha said to him, ‘I know he will rise, in the resurrection on the last day.’ ” (John 11:23-24). Jesus then reminds her that he himself is the resurrection and the life. It’s at this point that Martha professes her belief that Jesus is “the Messiah, the Son of God, the one who is coming into the world” (11:27).

So Martha, awakening from her sleep, demonstrates her faith, and in so doing gives us a window into the transition of the Old Covenant to the New – the practical activity of the Law coming to rest – as it’s actually happening. But she hasn’t yet fallen prostrate before the Son of God. It’s her sister Mary who does this. She’s the one who sits penitently before the Lord, anointing his feet with oil and drying them with her hair. It’s the lowly, sinful woman (if we are to identify Mary of Bethany with the sinful woman from Luke 7) who focuses her attention entirely upon Christ, looking solely to him for salvation. For this Jesus deems that “Mary has chosen the better part” (Luke 11:42). Though Mary is a lowly sinner still at the stage of purification, we understand that her repentance and complete devotion to Christ will lead onward and upward to higher things, to advanced contemplation of things intelligible.

Here we see the traditional interpretation of Mary and Martha come into view. It associates Martha with practical work and Mary with contemplation, which is in a certain sense the reverse of the schema I’ve been elaborating. I don’t mean at all to subvert the traditional understanding; on the contrary, my attempt here is to hold to it faithfully while highlighting some of the subtleties involved, which suggest that a kind of flip occurs when looking at the picture from a slightly different angle. If we look at Martha’s practical work, she represents purification – namely the purification of the Law. But as I’ve said, in her declaration of faith we see that purification brought to rest. This is the illumination of the Law giving way to the Gospel. If we look at Mary’s wholly focused attention toward Christ, we see contemplation. But when we take into account her current stage of development, we see a Christ-centered purification with the latent potential to come to full fruition in advanced contemplation. At the moment however, her understanding is still at the level of the sensible, and she weeps for the presumed death of her dear brother Lazarus.

This all just goes to show how tightly interwoven and interpenetrating these two sisters are as a combined symbol and how in the Gospels there is often a mysterious criss-crossing that occurs between high and low. A sense of this criss-crossing is given in the events flowing directly out of the Lazarus climax. Before the miracle, Mary wept. Her rational mind, conditioned toward the merely natural, was in need of the exchange of the Law for the Gospel. So it’s Martha, the illuminator, whom attention is directed to first. Her task fulfilled, Martha then ‘goes and gets’ Mary: “Once she had [professed her faith], she went and called her sister Mary secretly, saying, ‘The teacher is here and is asking for you.’ As soon as she heard this, she rose quickly and went to him” (11:28-29). The sisters then witness the Lazarus miracle, and Mary’s mind is activated toward upward development, toward contemplation. It’s at this point that she takes on the more prominent role of the two sisters. She anoints Jesus’s feet, while Martha continues to serve, more or less in the background. The higher faculty, formerly constrained to the Law, has facilitated the removal of the stone, unblocking the lower faculty to flowing upward toward even higher heights. The feet, though lowly, are emphasized and shown to have an exalted purpose – namely to be a strong and necessary foundation.

With the rational mind of man reopened to the noetic, the perimeter of grace around creation is reestablished and the doorway to God opened for natural things formerly circumscribed by the sixth day.

So Mary and Martha are indeed a 6 - 7 pair, and an extraordinary one at that. It’s Mary and Martha who exemplify man’s special role as lynchpin of creation connecting Heaven and Earth. With the intellective faculty now re-positioned, through faith in Christ, to open back up to what is beyond the merely rational and natural, the natural man and by extension the natural world are raised up, toward perfection. And thus we have our full first ‘big triad’:

It’s taken me a little longer than I expected to lay out this first big triad. While I’ve been contemplating these patterns for a good while, I’ve only recently begun developing them in writing, so this series is really an image of my thought process. I hope I haven’t strayed in making these observations. And if you’ve followed along so far, I hope you’ve found the exploration interesting and/or helpful. I think here we really start to get a sense for how these somewhat complicated patterns can be practically applicable, especially in the case of Mary and Martha who show us just how critically important faith is in the grand scheme of things.

In part 3 I’ll move onto the second big triad, and we’ll see the ladder St. John is constructing (or rather, I should really be saying “depicting”) come into full view.

You’ll recall from part 1 that I’m looking specifically at the Gospel of John because the 6 - 7 - 8 fractal is so clearly discernible in it.

Allusion to Jacob’s Ladder (Gen. 28:12).

We hear a version of this phrase repeated twice in Ch. 1, during the gathering of Jesus’s first disciples – firstly from Jesus to Peter and Andrew (1:39), then from Philip to Nathanael (1:46).

I’m using “fleshly” non-pejoratively here.

I say the first “direct” healing here to refer to the fact that there is another event that could be considered a healing, namely the second sign at Cana where Jesus tells the royal official that his son will live (4:46-54).

Maximus the Confessor. “Chapters on Knowledge,” in “Maximus Confessor, Selected Writings,” Trans. George C. Berthold, p.145. Paulist Press, 1985.

Jones, Cormac. “Art as food; on the preparation and consumption thereof.” The Cormac Jones Journal, February 2023.

One could quibble over the exact terms here, but I trust the reader will garner from context what I mean by “rational” and “noetic.”

Maximus. “Chapters,” p. 136.